————————————————————————————————

Monthly Discussion

One-to-One Substitutions Rarely Are Complete

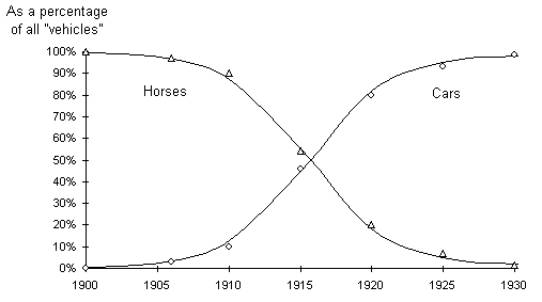

The mechanism of competitive substitutions was

described in Predictions as a

natural-growth process. The classical example of cars substituting for horses

in the personal transportation market showed how the market shares of horses

and cars followed complimentary S-curves between 100% and 0%, the former going

down and the latter going up, see Exhibit 3.

The Substitution of Cars for Horses

Exhibit

3. The data points represent percentages of

the total number of transportation units, namely, cars plus non-farming horses

and mules. The S-curves are fitted to the data points. The sum of respective

ascending and descending percentages equals 100% at any given time.

Based on the principle that niches in nature do not remain

partially full or partially empty under natural conditions, it is assumed that

one-to-one substitutions proceed to completion, which seems to be the case with

horses and cars. However, if we extend the tie horizon we find that the data

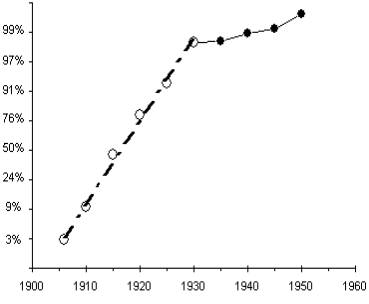

deviates from the natural curves. I Exhibit 4 we see the cars-for-horses

substitution in the logistic transformation that makes S-curves look like

straight lines. It is clear that whereas a perfectly straight line

(intermittent line) describes well the bulk of the substitution process, the

data points after 1930 (black dots) deviate significantly from the

straight-line pattern. This deviation indicates that the number of horses that

did not become substituted is much larger than the natural substitution process

would have forecast.

The Evolution of the Cars’ Market Share with Logistic

Scale

Exhibit 4. The logistic scale of the vertical axis

makes S-curve look like straight lines.

The straight line of the cars’ market share stops in 1930 beyond which

date there are too many horses (black dots).

In the cars-for horses substitution the deviation

from the natural-growth process sets in after the substitution is 98%

completed, therefore the deviation observed has little practical significance,

but more often than not such deviations are much more important.

Exhibit 5 is adapted from the celebrated article by

Fisher and Pry who first suggested that one-to-one substitutions follow

S-curves. I have updated the three substitution processes depicted in this

exhibit with recent data (something not done in Predictions - 10 Years Later).

Deviations from the straight-line patterns appeared

well before the end of the substitution process. For synthetic rubber

substituting natural rubber deviations began around 1980 when the substitution

had reached 76% completion. For synthetic fibers replacing natural fibers

deviations began around 1983 when the substitution had reached 72%, and for

margarine replacing butter deviations began before 1980 when the substitution

had reached 71.5%.

I fact for all three substitution process the final

settling level of substitution seems to be around 2/3 of the total.

Three Celebrated Natural

Substitutions

Exhibit

5. The black

data points represent recent data. They generally depict deviations from the

previously established straight-line patterns (S-curves). The

margarine-for-butter substitution (little squares) is graphed on the right

vertical axis. The vertical scales are logarithmic.*

CONCLUSIONS

Contrary

to what may have been expected from the law of natural competition, one-to-one

competitive substitutions do not have to proceed to completion. A “locked” portion of the market share seems

to resist substitution. In three publicized examples of natural substitution

this locked portion was about 1/3 of the market. I have seen even larger such portions. The case of market value

that shifted hands from IBM and Digital Equipment Co. to INTEL and Microsoft

between 1984 and 1994 was a substitution process that proceeded to only 50%.

Competitive substitutions are natural growth

processes and do follow S-curves, but the final ceiling rarely is 100%.

As

disconcerting as it may be when you see a threatening newcomer begin to cutting

persistently into your market share, there is no a priori reason to

interpret his or her gains as a sign of an eventual take-all.