————————————————————————————————

Monthly Discussion

The Evolution of the EU

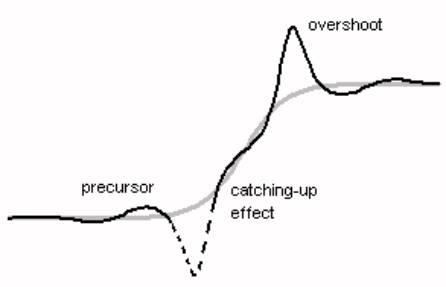

If the European Union is to ever achieve a state of nationhood, it must follow a natural growth process. The hallmark of a natural growth process is the S-shaped pattern I have amply describe in Predictions. But this smooth pattern that growth in competition theoretically follows, is often distorted in real life. Typical distortions are shown in Exhibit 3.

Exhibit 3.

The natural growth pattern often shows deviations from the S-shaped

pattern such as precursors, overshoots and catching-up effects, see Predictions.

The origin and real-life equivalent of

these deviations are rather evident. Precursors are unsuccessful early

attempts, often considered as failures. The quite period that follows a

precursor contributes to “pent-up demand” and results into a period of rapid

growth (catching-up effect). Finally, a well-established growth process may overshoot

and later fall back and settle at a lower level.

We may expect these phenomena in the

growth process of the European Union. In Exhibit 4 I graph all events related

in the construction of the EU, as reported in http://europa.eu.int/abc/history/index_en.htm published by

the European Union. The chronology includes all kinds of events, important

ones, like the introduction of the unique currency, as well as less important

ones, like the change of the presidency from one country to another. By putting

all events together in one data set we are defining an “index of activity”

relating to the formation of the EU. This index has been growing since

September 19, 1946 when Winston Churchill first called for a “kind of United

States of Europe”. The growth has been steady and turbulent accelerating

sometimes, decelerating at other times. But for obvious reasons, when maturity

is eventually achieved, this index must stabilize.

Exhibit 4. The number of events directly contributing

to the creation of the EU has followed an overall S-shaped pattern, while going

through smaller S-shaped patterns.

As in all sustained growth, the

evolution of the number of events that has shaped the EU has followed

successive steps. Each step, itself an S-curve, displays the deviations

expected in Exhibit 3. In addition, an overall S-curve of large time frame

(turquoise line) indicates that the growth process was 82.4% complete on March

1, 2003. One or two more small steps should be expected.

The consequences of Exhibit 4 are far

reaching, however, because can help us form a realistic estimate of EU’s final

size. There have been proposals and discussions that could extend EU’s borders

deep into Asia (e.g., with Turkey’s candidature), and even reach the Pacific

Ocean with Russia’s possible eventual inclusion. How much of his is realistic

in view of EU’s recent failure to present a united policy on the war with Iraq?

Voices have been occasionally raised for a 2-speed EU with a few “hard core”

states and many more “satellite” states.

Only 12 European countries have joined so far in all

respects, including monetary union. If 12 corresponds to 82.4% of the final

number, one estimate for this final number is 14 to 15, a number far below the

26 presently worked on. In this light talk about Turkey’s and Russia’s

admission to the EU sounds absolutely far-fetched.