————————————————————————————

Monthly

Discussion

Magnetic Levitation Trains (Maglevs)

The

world's first magnetic levitation train for commercial use, the Maglev, started

its regular service Thursday, Jan. 1, 2004 between Longyang Road Station and

Pudong International Airport in Shanghai, China (see article in

http://de.news.yahoo.com/040101/12/3tl9m.html).

The prediction that had been made in PREDICTIONS twelve years ago

concerning Maglevs was that around the end of the 20th century a new

“species” would enter the world transportation market and begin competing for

passengers with the other means of transportation. The specific prediction was

that Maglevs would “enter the market significantly around 2025, by claiming a 1

percent share of the total length in all transport infrastructures, and reach

its maximum rate of growth close to 2058”, see Exhibit 3.

An

Orderly Precession of U.S. Transport Infrastructures

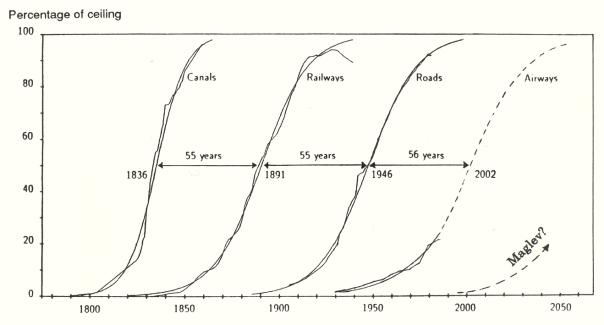

Exhibit

3. The growth in length of each infrastructure is expressed

as a percentage of its final ceiling. The absolute levels of these ceilings in

miles are quite different, for airways the ceiling has been estimated.

Interestingly the 50 percent levels of these growth processes are rather

regularly spaced 55 to 56 years apart. The Maglev infrastructure therefore may

start sometime around the beginning of the twenty-first century, but its

halfway point should be close to 2060.*

Today, besides the Chinese Shanghai

section, Maglevs are planned in at least seven states of the US. In Virginia

the Baltimore-Washington project plans a Maglev connection that would link

these two cities in less than 20 minutes. In California, the planned Maglev

will connect the Los Angeles International Airport to March Field in Riverside

County, a 92-mile distance in 78 minutes, and in Pennsylvania the

Pittsburgh-Greensburg connection (54 miles) in less than 35 minutes. All three

of the American Maglevs mentioned here are planned to come into operation

around 2010-2011.

These developments reinforce confidence in my old

prediction that Maglevs will claim a 1 percent share of the total length in all

transport infrastructures by 2025. From then on Maglevs will begin taking away

market share from the dominant air travel, see Exhibit 4.

Exhibit 4. The sum total in mileage among all transport infrastructures is

split here among the major types. A declining percentage does not mean that the

length of the infrastructure is shrinking but rather that the total length is

increasing. Between 1860 and 1900 the amount of railway track increased, but

its share of the total decreased because of the dramatic rise in road mileage.

The thin model lines are projected forward and backward in time. The share of

airways is expected to keep growing well into the second half of the

twenty-first century and begin declining only when Maglevs enter the scene in a

serious way (dotted lines). The small circles show some deviation between the

trajectories predicted fifteen years ago and what happened since then.*

Let me explain again here why Maglev constitutes a

new bona fide transportation species. The major inter-city

transportation systems so far have been successively: waterways (channels),

railways, highways (motor vehicles), and airways. Each time the new system

progressively replaced the old one as the dominant means of transportation

despite large overlap between different systems. But the competitive

requirement for a new transport system has always been that it must provided a

factor-of-ten improvement in speed or, more precisely, in productivity

(load times speed.) Supersonic travel as introduced by the Concord did not go

in that direction because while it did increase the speed it decreased the

payload, and even the speed increase was far less than a factor of ten. Future

supersonic planes based on new technology—possibly using liquid hydrogen as

fuel—may provide Mach 8 in speed but will be useful only for long distances.

Supersonic flight is obviously not the answer for linking cities within a continent.

Since speed of existing airplanes is sufficient to serve shuttle links such as

New York to Boston, the future vehicle must increase the number of passengers

by a factor of ten, the equivalent of the Boeing 757 or the European Airbus,

but with a carrying capacity of close to twenty-five hundred passengers! The

problems arising from handling that many passengers in one flying vessel would

be formidable.

The alternative is Maglevs. These

trains move at a mean speed of up to six hundred miles per hour, and from the

point of view of speed and running cost they are like airplanes. But they can

carry a much heavier payload. Maglevs should only connect core cities in order

to justify their high capacity and investment costs.

But at this point, a word about fuel

is in order. Transport is coupled to energy. The dominant means of

transportation at any given time is linked to the dominant primary energy

source of the time. The succession we see in Exhibit 4, waterways to railways

to highways to airways is coupled to a succession of primary energy sources

(animal feed to coal to oil to natural gas) also discussed in PREDICTIONS. Animals used to

draw the barges along the channels during the 18th century, coal was

the primary fuel of railways, oil the primary fuel of automobiles, and natural

gas the primary fuel of airplanes (aviation is young and still uses oil as

early railways used wood!)

This one-to-one correspondence between transport and

energy suggests that Maglevs should use the next primary energy source, which

is nothing else than nuclear energy. Today’s Maglev, and those in the planning

stage, are all powered by electricity. But electricity is not a primary energy

source. It can be produced in a variety of different ways. Today it is largely

produced by burning oil and in the future it will be produced by burning

natural gas. In late 21st century it will be mostly provided by

nuclear reactors. By that time nuclear energy will be the dominant

primary-energy source. It will probably

also be providing in a direct way the hydrogen needed for advanced-aircraft

supersonic travel.

Substitution of Primary Energy Sources Worldwide

Exhibit

5. This

modeled substitution of energies is obtained from PREDICTIONS. The intermittent

line represents animal feed only for the US. “Solfus” is a futuristic energy

source combining solar and fusion.