LOUISE’S DOUBLA

A family story by Theodore

Modis

I am sitting by my mother’s

hospital bed. She is 95 years old. When her temperature goes up she sometimes enters

a state of delirium talking, singing, reliving old memories, or venturing into

new fantasy ones. At these moments I am reminded of my grandmother who at the

age of 86, and due to no diagnosed illness, she permanently entered a fantasy

world. What triggered that event was a technological development in the

recording media.

In the mid 1950s the first

local radio station made its appearance in Florina, the little town of northern

western Greece where we lived. One of the first programs the radio station

aired was an interview with Paraskevi Modis. I remember the radio-station staff

showing up at my house with some cumbersome equipment they called tape

recorders. They were interested in my grandfather’s life, and in particular

they wanted that Paraskevi sing for them the folkloric grassroots song that

emerged spontaneously when her husband was assassinated. She did, they recorded

it, and then played it back to her. That was it! She went into a crisis about the “devil machine that took her

voice” and the next day she snapped into her fantasy world.

At the turn of the 19th

century my grandfather, Theodore Modis, was a prominent merchant of Monastiri

(today Bitola in the Republic of North Macedonia), a commercial

junction in the southern Balkans under Turkish occupation at that time.

Turbulence was brewing, however, as the Turks were preparing to leave. The

Ottoman Empire retracted leaving behind disputed land. Greeks, Bulgars,

Albanians, and Serbs organized themselves into committatos. My grandfather

was head of the Greek committato.

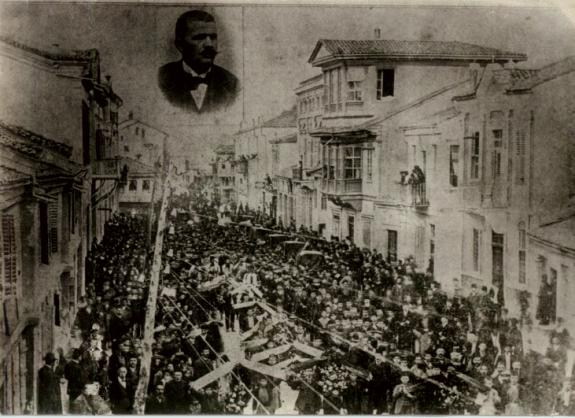

The publicized funeral of Theodore Modis in Monastiri

in 1904.

On September 5, 1904 someone

entered the office of Theodore Modis and shot point-blank at him. The event

marked the formal beginning of the Balkan wars and my grandfather was declared

a Greek national martyr. As for Paraskevi, she did not accept her husband’s

death peacefully. She decided to enter the armed struggle, transformed her

imposing three-story house into guerrilla headquarters, and supported the Greek

fighters in every possible way. It wasn’t long before her house became target

of attacks. Eventually a targeted bomb set the house afire. At the last minute

Paraskevi threw out of the windows whatever valuable could be saved, stashed

everything on a horse-drawn carriage, including her two small children (Yorgo

an Aglaia), and headed south toward already liberated Greece.

Among the “valuables” she

tried to salvage at the last minute was … well, a dress!

Paraskevi was a beautiful

woman. Light complexion, rosy chicks, and sky-blue eyes. Her looks had become

legendary when at 22 she was seen at her window by passing Theodore who

promptly asked for her hand. Their life as a couple was glorious, furious, and

short. Well-to-do Theodore owned the biggest house in Monastiri, bought

extravagant clothes for his wife, but was also fiercely jealous of anyone

setting eyes on her. For her part, Paraskevi, was self-asserting,

strong-willed, and at times she concealed a gun in her bosom and even slept

with it. The couple quarreled often, and rumors say that on one occasion she

had her husband at gunpoint.

Paraskevi and Theodore Modis in the late 1890s.

Coquetry was not the reason

Paraskevi tried to salvage a dress while her house was burning. And yet, preoccupation

with dressing ran in the family. Theodore’s grandfather—this is Yorgo’s

great-great-great grandfather—most probably also named Theodore according to

the strict tradition of passing first names from grandparent to grandchild, was

extremely concerned about his dressing. His last name was not Modis at that

time but some weird long difficult-to-pronounce name that my grandmother once

told me and I forgot. But Yorgo’s great-great-great grandfather made a point to

follow and dress according to the latest fashion. To keep up with trends he

regularly ordered fashion magazines from Vienna for his tailors. Before too

long the nickname Modis (from mod) was slapped on him and eventually

became his last name.

However, the dress Paraskevi

tried to salvage had more pragmatic value. It was a traditional Balkan dress

decorated with golden coins. Several lines of golden pieces had been sewn in

rows decorating the bust of the dress. The arrangement had small coins at the

extremities (grossia) and progressively larger ones (flouria)

toward the center. The row with the biggest coins doublas (from

double)—pronounced as in hoopla—weighted heavily and had corresponding market

value.

When I first set eyes on the

garment as a little boy, large parts of the lower dress were missing. In the

decades that followed, the garment would surface on occasions and another

golden piece would be cut off for a special purpose (at some point, my mother

removed a whole bunch of them to supplement my sister’s dowry). The last time I

saw the garment Louise’s doubla came off. By now the one-time fancy

dress resembled a rag.

Louise’s doubla.