IN THE QUEST OF YORGO’S BAPTISM CERTIFICATE

A true story by Theodore

Modis

Contrary

to English-speaking people, Greeks are not familiar with foreigners speaking their

language. In fact, Greeks are often astonished and also flattered when they

hear Greek spoken with a foreign accent. That was the first indication of

something unusual with my quest for Yorgo’s baptism certificate. When I called—Moni Vlatadon—the church in

Thessaloniki where Yorgo had been baptized the voice on the other end of the

wire spoke Greek with a foreign accent.

The next morning I set out in my

sister’s 31-year old VW beetle for Moni Vlatadon to take things at hand in

person. “Moni” means monastery in Greek and that is what this church complex

used to be centuries ago. Today the set of buildings perched on the top of a

hill just below the old ramparts enjoys the most splendid view of the city and

the entire Thermaikos bay. Principal role among the buildings plays the small

church at the center dating from the early XIV century. It is a Byzantine

church of the cross type with a dome. The interior of the church is covered

with remnants of wall paintings rich in ascetic figures with golden auras

around their heads, large sad eyes, and long fingers. But less than 20% of the

works remain intact. The rest bears the marks of willful violent destruction.

The Turks occupied this land for 400 years and the continuous belligerence

between the two people had its toll.

When I arrived at the small church

its door was open but there was no one inside. It was 11:00 am and even if

there had been a mass, it was reasonable that everyone had gone home. An old

short bald man in the courtyard told me that I should address myself to the

offices and pointed at a building hidden among trees below. In the patio of

that building I met the first priest.

He was tall, with short blond hair

and blue eyes, in his early twenties. The long black clerical garment tied high

at his waste gave him a theatrical air. It was obvious to me that he came from

a Nordic country (northern than Greece anyway) well before he revealed his

foreign accent. When I told him the reason for my visit he paused and looked at

me with a good-nature smile for a long while. I felt awkward and began

preparing to make a fool of myself by repeating my question. Eventually he

spoke with a soft almost melodic voice. “If you are able, you should come back

at 6 pm and talk to father Nik…,” he said. “He is the one who baptized Yorgo

and will be able to help you.” I

protested, “But this baptism took place 28 years ago. Can it still be the same

priest?” not realizing that I had not retained the father’s name”. “It is all

right”, he reassured me, “That’s about how long he has been around here. You

should come back at 6.”

Before getting back to the car I

walked around the grounds and gazed at the city and sea below. Memories of that

singular date came to my mind. Yorgo had been baptized on the day the Turks

invaded Cyprus. There had been no warning. After the baptism ceremony we had

gotten in our cars (Agla’s very VW beetle among them) and were heading for a

scenic restaurant when I turned on the radio. Unusual military-march music on a

Sunday morning. Soon came the announcement of the country’s first general

mobilization since World War II. What tumultuous times!

That was my way of pinpointing the

date of Yorgo’s baptism. I had asked a bunch of Cypriot students back in Geneva

and they had told me “July 20, 1974”.

Driving back into the city from

Thessaloniki’s old town is even more complicated than getting there in the

first place. The irregular downward alleys generally give the impression they

lead to a dead end and yet there is always a way out, barely, with cars parked

in all conceivable places and ways. Impossible to retrace the way I came. I had

to guide myself with gravity, following the path a drop of water would follow

to get to the sea.

The same day at 5:45 pm I was back

at Moni Vlatadon. It was dark already and the gate of the church parking had

closed. I parked on the street outside and walked directly to the church.

Lights, candles, and a handful of people. Suddenly I see a fleeting young priest

with a dark beard. “Excuse me, where is the father”, I asked (he was too young

to be the father I was looking for). “Which father, there are many of us here”,

he explained and disappeared without slowing down. Did he have an accent? I

wasn’t sure.

I notice the same old short bald man

sitting behind the counter with the candles for sale. He turned around reached

above his head to a sequence of white buttons on the wall and pushed the first

one. A bell began ringing. I walked around inside the small church several

times over. At some point I bumped into an older priest wearing light beige

clothes (could he be a catholic!) I demanded his attention and made my request.

“You should go to the city office of the registry for such a certificate”, he

said. “After you baptized your son you registered him with the city’s offices.

They will give you the certificate”.

I know that after I baptized my son,

my sole concern was to get out of Greece and back to Geneva as soon as

possible. In fact, I remember distinctly a desperate frenetic drive that day

directly from the scenic restaurant to the Yugoslavian border 60 kilometers

away in a fruitless attempt to get out of Greece before the borders close.

There was no way I would have taken any baptism papers to any bureaucrats in

any city offices during those times.

So I protested. “No, I have not

registered my son anywhere. You must help us find a copy of your records here.”

Reluctantly he said “If the deacon comes later on, he can go and fetch the

books” and disappeared. Were all priests mercurial like this or was it only

this particular bunch there on that night? There was something about that

night. I wandered some more inside the church. More people were coming and a

young man with an adolescent face entered and took place by the sanctuary. “Are

you the deacon?” I asked. His voice was younger than adolescent; more like

someone’s before puberty, a female voice, so soft I had to lean forward. “You

mean Father Peter?” he asked, “No I am not”. He was obviously one of the chanters.

“How will I recognize him?” I asked. “Well,” he hesitated, “he is wearing a

cassock”, and balanced his hand down his side as to sketch the flowing garment.

While I walked up and down the

church like an impatient tourist, the commotion kept increasing. More older men

gathered around the old short bald one. More people arrived, most of them weird

(for this part of the world) long beards, backpacks, redheads, blacks, and some

who looked “normal” but behaved unconventionally (an agitated young lady who

spoke too loud, a guy who was limping but wanted to perform deep bows in front

of every icon, etc.) At some point the old short bald man asked his friends,

“Shall I ring them all”, and turned around reached over his head and pushed all

seven white buttons one after the other. A chorus of bells! It was 6:00 pm.

People turned toward the church entrance with anticipation. And there it came.

A group of five young priests all dressed in the long black clerical gowns

escorting an old imposing central figure wearing a despotic hat covered with a

black scarf. Could he be the priest I am looking for? Obviously not. He seemed

way too important. The bells stopped, the black crowd walked toward the

sanctuary and the despotic figure sat on the bishop’s throne. Could he be a

bishop?

I finally understood. I was

partaking in a vesper and an extraordinary one at that. A number of chanters

began to chant and soon they addressed the imposing older cleric as Archbishop

Panteleimon. Amazing! I was familiar only with the controversial Archbishop

Christodoulos of Athens, who mingled in politics as if he were at least

minister of the interior. Then I remembered that Moni Vlatadon is unique in

Greece as a church that answers directly to the Patriarch in Constantinople

(the Patriarch for Greeks is the ultimate religious authority as the Pope is

for Catholics.) I began wondering about the ramifications of an archbishop

doing a vesper in this small church on this particular day.

In the meantime just about everyone,

except me, had lit a candle and made the rounds bowing in front of and kissing

every major icon in display. I remembered my mother’s words. “When you are in

the church, do light a candle. It may even help you get your certificate

faster.” I decided to go through the ritual. I bought and lit a candle. As I

was about to kiss the icon displayed at the most prominent pedestal another

blond young priest appeared, this one with long hair clinging to his scull. He

swiftly picked up the icon in front of me, removed the frame around it that

seemed to be simply sitting on it, turned the icon upside down, placed an icon

he had brought with him on it and replaced the frame. He bowed, kissed it, and

began moving away. I ran after him. “Do you know Father Peter, the deacon?” I

asked. “That’s me”, he said in a melodic female soft voice and an unfamiliar

foreign accent.

“Please, I need a baptism certificate for my son who

was baptized here 28 years ago.”

“You should talk to Father Nikiforos.”

“I did and he said you should bring

the books”, I could not believe my audacity.

“I will”, he said moving away.

“When?” I almost shouted.

He turned around while moving away,

looked at me over his shoulder and said with gentle annoyance “Not right now”.

I am not very religious and I rarely

go to church, (I never miss the highlights of a midnight Easter mass, however.)

But having to sit through an entire vesper in the middle of November seemed to

me exaggerated. When I saw the old short bald man going outside I followed him.

“What is the best time to catch Father Peter”, I asked him.

“He was just there changing an icon”

he exclaimed.

“Yes, but he goes through my fingers

like mercury”, I complained and explained my problem to him.

“Come tomorrow morning. You will

catch him after the mass at 10:30.”

After a mass cannot be different

than after a vesper, I thought. I might as well stick it out tonight and use

tomorrow as a fallback solution. Back in the church the archbishop was getting

angry at the chanters. They were making mistakes and he corrected them bluntly

over the loudspeaker. “Not now!” he would shout. “Now, Kyrie Eleison, Kyrie

Eleison, Kyrie Eleison.”

Vespers are much shorter than

masses, I found out. At some point the cloud of long-dressed black figures led

by the archbishop left the church with me running behind them hoping to catch

Father Peter. He saw me and stayed back to talk to me. “I will bring the books,

but I don’t know when father Nikiforos will have the time to do a search,” he

said.

“Shall I come back tomorrow morning?” I suggested.

“I don’t know, come if you want”, he answered

capriciously, and added “Why don’t you first call Father Nikiforos at 209913.”

I had no pencil and paper but this time there was no

way I was going to forget the father’s name or the phone number.

Driving home it was statistically

impossible to follow the same way as in the morning. Too many little streets

going in too many different directions. I again oriented my trajectory

instinctively toward the sea. When I finally ended up on a one-way main traffic

artery, a bus line with three lanes, I thought my problems had been solved.

Wrong! Many illegally stopped or parked cars, trucks, and other vehicles on the

right and left lanes forced the busses to conduct their stops in the middle

lane. It took twenty minutes to cover one kilometer.

The next day was a major religious holiday, Virgin

Mary’s entrance to the temple. On my way to Moni Vlatadon, the radio-station

speaker was wishing happy name day to all Marias, Marys, etc. That is strange, I thought. I know at least

one Maria who celebrates her name day on August 15. I arrived at Moni Vlatadon

at 10:30 am in time to have missed the mass but not its aftermath. I drove into

the compound’s grounds and parked in its privileged parking area. Walking the

courtyard I bumped into the old short bald man again.

“Where were you last night”, he asked. “Father Peter

brought the books and was looking for you?”

“But he told me to call first” I began apologizing

when I perceived the young priest with the dark beard (Father Filippos, as I

later found out) rushing out of the church. I caught up with him and began the

recitation of my request. “I will do the search”, he interrupted me “but not

immediately. I need to spend some time with the bishop first. If you can wait,

you may come and sit in the office.” I followed him into the old building in

the trees.

The old building was loaded with past-century wooden

furniture, each piece in excellent condition. Tables with sculpted legs,

showcases with distorting windowpanes, coat hangers with snakeheads sticking

out to hang your hat on, and so on. The room he ushered me into had two desks

and a small bench strangely reminiscent of a love seat. On one end of the bench

you could access a computer and printer (latest technologies) sitting on a

small side table with a single twisted central leg. The fewest cables possible

were visible for such a setup.

I sat on the bench and began to wait. The door was

open and so was the door of the room across the hall where much activity was

taking place. I could not see but could clearly distinguish the voices of

several people. Apparently a central older figure (bishop?) was speaking as if

lecturing while several young priests served as audience in a relaxed

atmosphere with Greek coffees and glasses of water coming and going. The older

voice spoke in katharevousa (archaic Greek); the young voices generally had

foreign accents, one of them rather familiar to me. The talk was about Greece,

culture, religion, world events, etc.

Half an hour went by like this. A cell phone on top

of one of the desks next to me began ringing in the most discrete mode, i.e.,

as a vibrator. It rang for a long time. Before it stopped, Father Peter rushed

in and picked it up. How on earth did he hear it from across the hall and with all

what was going on. He began talking softly in an unfamiliar language. Many

“tchi” sounds; Rumanian? Slovenian?

A little later, Father Apostolos came in with a man

trailing behind him requesting a recommendation letter. The priest sat in front

of the computer and turned it on. Windows XP showed up on the screen! At

that moment Father Filippos came in looked at me benevolently and began: “Let

us see now. When was your son baptized?”

“On July 20, 1974, the day on which the Turks invaded

Cyprus”, I exclaimed.

“And you are back here to ask for a baptism

certificate on the day the Cyprus problem is about to be resolved!” he said,

obviously alluding to the plan just proposed by UN Secretary General Kofi Annan

for a solution to the 28-year old Cyprus conflict.

I knew his accent very well and yet could not

identify it.

Alas! The books went back only to 1976 and there was

no way Father Filippos could locate earlier records. He suggested that I go and

try the city office of the registry. “But what happens if they don’t have

anything there”, I argued knowing too well that I had not furnished that office

with any documents.

“In that case, we will have to make up a new one and

bring it to them”, he said.

“Why don’t we do this right now, so that I won’t have

to come back here”, I dared suggest.

“Do you have all the information needed?” he asked

reluctantly.

“Yes, of course!”

At this point there were three young priests in the

room. Father Peter was walking around with the cell phone still softly speaking

in …?, Father Apostolos was on the computer typing the recommendation letter,

and Father Filippos was waiting on me. Suddenly a young couple entered the

room. A big Russian-looking woman and a tall well built shy man. Father

Filippos apparently knew them.

“You are here for the document and also the matter

you want to discuss with me?”

“Yes, please”, replied the woman with a coarse manly

voice. She was unquestionably Greek.

“And the matter you want to discuss is confidential?”

“No, it is not confidential”, she said defensively,

but then added “I just need to discuss things only with you”. She obviously

needed some privacy but could not find such a word in the Greek vocabulary.

“Then you don’t mind waiting while I

finish with this gentleman first”, he said pointing at me.

“Not at all”, she replied, taking a

seat next to me.

Father Filippos began filling a

brand new baptism certificate.

“What shall we use as a protocol number”, he

wandered.

“Use a number smaller than the first number of year 1976”,

was my fine idea until I realized that the first number was 1.

“What is the date today”, he asked

“November 21”.

“Well, what do you say that we take 22 as the

protocol number”, he looked at me smiling.

“Sounds good!”

“Who was the priest?”

“Hmm, I am not sure, but he was probably the same one

as in early 1976.”

“Father Nikodimos?” he asked after consulting the

book.

“Coming to think of it, Father, the name sound

familiar to me”, I said shamelessly.

As we proceeded filling out the form, it came to me. He

had a typical Greek-American accent. “Where are you from Father?” I asked.

“From New York”.

“I lived in New York for eleven years while studying

physics at Columbia. Where in New York are you from?” I immediately realized I

was pushing my questioning too far.

“Well, … somewhere in Queens.”

He was obviously from Astoria, the Greek town in

Queens.

“And you, what do you do?” he asked.

“Futurology”, I snapped, “I write books and make

market forecasts”.

“How interesting!” exclaimed uncontrollably the

Russian-looking Greek woman. “What is the title of your book?”

All three priests stopped what hey were doing and

looked at me. There was a moment of silence. Father Filippos spoke first. “I

imagine you work in a scientific way.”

“Yes, of course, my approach is scientific”, I

reassured them. “I have simply become accustomed to employing a provocative

vocabulary in order to capture my clients’ attention”.

There was more information missing

for the document under creation, namely the reference number on Yorgo’s birth

certificate. But the document was finally completed to Father Filippos’

satisfaction. He stamped it as “exact copy” and signed it.

“Please don’t show his document to

anyone until you have been convinced that there is no record of your son’s

baptism in the city registry”, he pleaded. “Also, you must first pass by the

All Saints Church and buy three ecclesiastical stamps that you will glue on

it.”

I felt obligated. I thanked him

profusely and asked for instruction to the All Saints Church. It is on the other

side of the railroad station, itself on the outskirts of the city. Finally, at

the doorstep I remembered to ask instructions for the city registry.

“Tantalou 30 is the address”, was

the answer. But where would that be? None of the priests had a good idea. At

that moment the shy companion of the Greek woman whispered things to her ear. I

thought he spoke in English. Then she volunteered instructions to me referring

to hotels, nightclubs, and fancy stores, none of which I knew. I thanked her

and left, ran to the car, and sat cap westward. A train station should not be

difficult to find.

The All Saints Church is a large Byzantine basilica

with a dome. Two rows of columns define three corridors. The larger main

corridor leads to the sanctuary at the east end of the church. The church was

empty when I got there but it was obvious that it had been massively occupied

very recently. There was one middle-age woman dressed in a gray suite wandering

among the seats with eyes shining as if from tears. I approached her and asked,

“Is there anyone here?” fearing she may give me a deserving answer.

“They are all gone”, she said. “There may still be

someone in the sanctuary” she added, pointing at the deep end of the church. I

walked to the sanctuary, which is overloaded with icons, overhead hanging

lanterns, and golden-paint decorations. There is one main entrance so heavily

ornamented that forbids you from setting eyes on it. The two side doors are

more approachable. They are covered each with a floor-to-ceiling icon of a

saint. I approached the southern door and hesitated. Can one knock at the door

of a sanctuary? Could that be considered blasphemous as if testing whether God

is inside? And how does one knock on an icon door? Where would I tap my

knuckles on the saint’s face, belly, or legs? I couldn’t bring myself to knock

at that door. Nor to push it open.

I retreated to the center of the church from where I

heard footsteps upstairs. There are two long balconies one above each corridor

defined by the two lines of columns. Someone was walking briskly on the

southern balcony but was well outside my field of vision. I desperately looked

around for a staircase but there wasn’t any. I ran outside the church hoping

there was a side entrance. There was one, but it was chained and locked and

there was so much dust on it that it could not have been used recently. I ran

back inside the church fearing that the footsteps may disappear, and indeed

they had. My frustration kept increasing. What was I supposed to do?

Suddenly the black figure of a hurried woman

appeared. I ran after her asking whether I could buy ecclesiastical stamps

here. “Yes” came the answer but without turning around or looking at me she

swiftly unlocked a door by the church’s entrance and disappeared inside leaving

no chance for me to follow. A little later she came out, locked the door again

and directed herself to the other side of the church’s entrance saying, “This

way”. I followed her as she walked noisily and clumsily. She was dark-haired, in

her late twenties-early thirties. Her black shoes had wide heels that could be

fashionable. She was wearing a black jacket that could be leather. Her dark

gray knee-length skirt covered black tights that could be sexy. Her face was

void of all jewelry or make-up. She looked as if she had just woken up and had

dark circles under her eyes. She could be attractive. At that thought, Angela’s

latest joke came to my mind in a reflex:

[God

first created the world and saw that it was good. Then God created the man and

saw that he was good. Finally God created the woman and saw that she needed

some make-up.]

In front of another locked door she tossed her

substantial key ring until the right key came up and unlocked the door. Once

inside the office she sat at a desk and I asked for three ecclesiastical

stamps. “Why three” she asked, “we usually put only one.” Her voice had the

familiar-by-now soft-spoken soothing tone of the people in this milieu. I

showed her the document at which point she concluded, “Maybe because it is a

copy. Anyway, here are three one-Euro stamps, it will be five Euros”. She tried

to wet the stamps by pressing them on a sponge pad that was completely dry. She

turned around opened her black handbag pulled out a small bottle of mineral

water and poured some over the sponge. (I was right! She could be attractive.

All modern young women carry bottled water in their handbags.) She lined up the

stamps on the top right corner of the document, glued them, and then searched

for the right rubber stamp among an assortment of stamps hanging from a

rotating rubber-stamp hanger. CANCELLED got printed in blue ink across the

glued stamps. “There you go”, she said handing me the document. “Thank you”, I

said walking away, “good buy”. “Sto kalo na paate” was the well-wishing

greeting she gave me equivalent to “may you go in peace.”

I got back to the car and reached

inside my pocket for the car keys. I felt an unfamiliar small package. I pulled

out a soft bundle with Greek arts-and-crafts wrapping paper. “What the hell was

that?” I squeezed the package gently trying to guess its content and origin. I

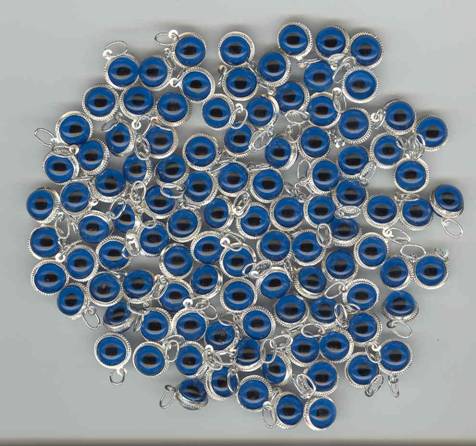

remembered with amusement: one hundred matakia, the equivalent of an

anti-evil-eye bomb! A mataki (little eye) is a small spherical blue

glass bead with a dark nucleus framed by a fine silver wreath with a tiny loop.

The mataki, when worn, protects the bearer from evil-eye

mean-wishers. It is recommended as essential garment in situations where envy

may be provoked inadvertently—by your good fortune—or advertently—by your own

hubris (known to ancient Greeks).

I had forgotten that between trips to Moni Vlatadon I

had bought 100 matakia for the candy wraps of Yorgo’s and Louise’s

wedding. The next instant a new realization struck me. I had been visiting

churches and holy places with massive magicware on me! The young priests had

flinched at my pronouncing the word futurology. What would they have done had

they known what I was carrying in my pocket? But then again, isn’t it true that

I had to crisscross the entire bazaar-like market of Thesaloniki before

locating the true matakia only in a store specializing in

ecclesiastical items?

I got in the VW beetle and plunged once again into

the self-governing traffic. Ian Fleming once referred to Thessaloniki as a

hideous junction. He must have been inspired by the city’s railroad district.

Heavy commercial and passenger traffic, doped with crowds of loose pedestrians,

yielded a viscous mixture that oozed in all directions. I agitated trying in

vain to beat the average moving speed. I was stuck behind a trailer truck

impossible to pass.

It was 1:00 pm and I was getting worried the city

registry may close. The Russian-looking Greek woman had said that the city

registry closes at midday, when people have lunch, which in Greece can be anytime

between 2 and 3 pm. She had given me instructions how to get there. Did I

remember them? I certainly remembered her concluding advice: park the car

whenever you can and search the building on foot.

The trailer truck in front of me

slowed down annoying me further. Its flashing light indicated it was going to

turn left. No. Incredibly it was trying to make a U‑turn. I thought this

maneuver was forbidden, if not impossible, for trailer trucks. With its trailer

wheels crossing over the dividing barrier the huge wobbling vehicle got out of

my way revealing no better traffic conditions. To my right there was a large

tourist Pullman bus double-parked but right behind it I saw an empty

angle-parking slot. I slid the VW in the slot apprehensive about the possibility

of the bus backing just a few centimeters and blocking me forever. But there

was no time to waste. I locked the car and continued on foot.

The registry office consists of a

sequence of window tellers facing a long table on which there are piles of

application forms. When I arrived all remaining forms were mixed together, and

there was not a single one labeled baptism certificate. A number dispenser was

offering numbered tickets for keeping track of the first-come-first-serve

principle unknown to Greeks during my youth years. I took a ticket and looked

it. Besides the large number, the date and the time were also printed on it.

Modern civilization finally arrived in Greece, I thought, and then noticed in

fine print “average waiting time: 11 minutes”. I couldn’t believe it! The

number-dispenser machine electronically calculated and updated an expected

waiting time. The Swiss post office (recently recognized as the most efficient

post office in the world) has number dispensers that are made in Sweden (another

most civilized country) but they don’t update and print the average waiting

time on their tickets.

I told the teller there was no form for a baptism

certificate but he insisted that I needed a certificate of marital status

instead, on which the religion is also mentioned. It took me a long time to

convince him that what matters in Ireland is not marital status but baptism. We

got into a discussion on the relative importance of these sacraments in

different cultures. Finally he suggested that I use the application form for

marital status, but cross out the title and replace it with baptism

certificate. Then he asked me for the year and the name; strangely not the

date! He pulled out an enormous heavily used handwritten book. “Under Modis I

have a Yorgo-Eugene”, he shouted, “could that be him?” I was flabbergasted. Not

only the record was there but also it had been entered alphabetically in a

handwritten yearly book! How did they do that? Did they collect records all

year long and enter them only at year’s end?

I took a seat and waited. At the

moment the teller called my name I also heard behind me “Here we meet again”.

It was the Russian-looking Greek woman and her companion. She was glad to see

me again but her snappy remarks and brusque manners revealed that something had

gone wrong during her “confidential” discussion with Father Filippos. Her

companion was trying to console her in English spoken with a heavy Slavic

accent. I bid them goodbye, obtained my two copies of the baptism certificate

and was directed to a maze of corridors and offices searching for the

authorizing stamp and signature.

When I returned to the VW my fears had proven

justified. The huge Pullman bus was now blocking my car. Frustratingly, I got

into the car and tried to honk the horn. No sound came out. The horn must be

one of the car parts that unfailingly become worn out after 31 years of

operation in Greece. While building up courage for my next confrontation I

noticed movement in the rear-view mirror. The bus was slowly moving. It moved

just enough so that I could drive away.

I did not feel the need to give thanks or to

acknowledge whoever’s consideration. I was becoming acclimatized to this city’s

modus vivendi where modern technologies and undisciplined individuals

blend to produce an incongruous concoction that somehow works. It could be the

simple fact that fundamental laws, such as survival, carry more wait than

regulations and technological breakthroughs.

Having obtained Yorgo’s baptism

certificate I no longer felt a sense of urgency. I decided to drive home along

the scenic seaside boulevard. It is the most beautiful road in Thessaloniki,

equivalent of the Promenade des Anglais in Cannes. It was another

typical gorgeous day with plentiful sunlight and bright colors. The sky was

sharp blue and the sea turquoise green. The horizon seemed at arms length, a

well-defined separation of colors hinting at a subliminal curvature. Mount

Olympus rose in the distance on my right with snow on its cap, some sort a

local Mt Blanc. I was reminded of a similar landscape in Geneva.

I rolled down the windows to get more of my senses into the action. How different was the smell of the sea from that of the lake. At this time of the year Geneva’s post-card pretty scenery carries melancholic overtones. Its lake can be horizonless with everything in shades of gray and no clear separation between water, mountain, or sky. Here everything was crispy, well defined, focused, in glowing color. It gave the impression of being in a Technicolor movie. Not quite. There was a perceptible difference. These colors were real.

God has blessed this land with His grace!

Yorgo’s baptism certificate was in my pocket!

Agla and mother were waiting for me with pitta in the

oven!

Quel pied!